Potato grower Brian Kirschenmann bent over the deep green plants in his field in New Cuyama, nestled in a verdant valley an hour southwest of Bakersfield, and looked at the bottom of each leaf.

Next to him, his crop advisor Gary Toschi examined a leaf under a magnifying glass.

“That one is active,” said Toschi.

An adult potato-tomato psyllid surrounded by young nymphs. Photo: Jeffrey Bradshaw, Univ. of Nebraska, Lincoln.

He and Kirschenmann had found a round, bright green insect, about the size of the comma on a computer keyboard. The tiny pest is called a potato-tomato psyllid, and both the young nymphs like the one they found, and the adults, which are shaped like a cicada, wreak havoc on potatoes, as well as tomatoes, peppers and about 40 other crops.

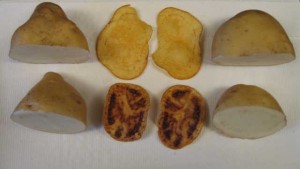

In potatoes, they suck the plant dry. And what’s worse, the pest also can transmit a disease that ruins potato chips – a $6 billion business in the United States, despite the bad rap chips get from nutritionists. The disease transmitted by potato-tomato psyllids gives chips a burnt flavor and causes them to develop brown streaks, which is why the disease is known as “zebra chip.”

Potatoes infected with zebra chip disease streak when they’re fried. Photo: John Trumble.

In 2008, Kirschenmann lost $250,000, when one of his potato fields in Kern County was infected with zebra chip and Frito Lay wouldn’t buy his chipper potatoes. Though potatoes aren’t one of California’s main crops, in Kern County they’re among the top 10 in value, to the tune of $130 million.

Zebra chip disease hasn’t caused widespread losses in California, but the state’s potato growers are worried, especially after South Korea banned potato imports from Washington, Oregon and Idaho in August, out of concern over the disease. The ban is costing producers in those states some $8 million.

“That’s my biggest fear,” said Kirschenmann, who grows 5,700 acres of potatoes in Kern County and New Cuyama and is a member of the United States Potato Board. Though California doesn’t export potatoes to South Korea, Kirschenmann does sell part of his crop to Guatemala and the Dominican Republic.

Potato grower Brian Kirschenmann.

California has had potato-tomato psyllids for more than 100 years. What makes them a new problem for growers is that now they don’t just live in the state during the warmer months; they also spend the winter.

“Our temperatures have increased by 2 to 3 degrees Fahrenheit, and that seems to be enough to keep them from being frozen out during the winter,” said entomologist John Trumble, of the University of California, Riverside. “I suspect that global warming is at least playing a role in this particular insect’s spread into California.”

Insects can’t produce their own heat, the way mammals do, so most of them do better in warmer temperatures. Around the world, scientists have started to document changes in insect behavior, as a result of climate change.

Entomologist John Trumble, from UC Riverside, says warmer temperatures are making a pest of potatoes and tomatoes more abundant in California.

In Spain, the European grapevine moth is flying out earlier in the summer and reproducing more abundantly than it did 20 years ago. On Tanzania’s Mt. Kilimanjaro, malaria mosquitoes are moving farther up the mountain. And in Japan, a pest called the green stink bug, that damages rice and soybeans, is expanding its range northward.

“This is not speculative, this is not something that we would predict,” said Trumble. “This is what’s happening now.”

When Trumble discovered, in the year 2000, that potato-tomato psyllids had spent the winter near one of his research tomato fields in Irvine, he knew this change in the insect’s behavior was bad news: it meant the pest could begin attacking crops early in the growing season.

“It’s much more dangerous for the grower,” said Trumble, “because early infestation in a crop oftentimes leads to much more damage than if the pest occurs late in the crop.”

When spring temperatures get warm, this sends a cue to insects to begin their development, said entomologist Peter Oboyski, manager of collections at the University of California, Berkeley’s Essig Museum of Entomology.

“If the season gets warmer earlier, that gives insects that much more time to develop, that much more time to eat a plant, that much more time to produce another generation,” said Oboyski.

Potato-tomato psyllid. Photo: Jack Kelly Clark, courtesy University of California Statewide IPM Program.

But how did UC Riverside’s John Trumble know that he was seeing a new behavior in the psyllid?

To figure out if spending the winter in California was a new behavior, Trumble turned to the historical record. He was fortunate that scientists in California have been collecting psyllids and making detailed notes about their habits since the 1880s. Through this information, he concluded that he was seeing something new.

“Every 30 years, since about 1900, it’s moved into California,” said Trumble, “and we would find it, it would be here for six months to a year, and then it would disappear, presumably because it got too cold.”

That pattern changed radically in 2000, with the psyllid spending the winter in Trumble’s field in Irvine. And the pest has since overwintered in locations further and further north.

In 2004, tomato growers discovered psyllids had overwintered in Hollister. In 2012, scientists found they had spent the winter in the Washington-Oregon-Idaho area, where half of the country’s potatoes are grown. And this year, the pest also appeared in Manitoba, Canada, early in the growing season, a sign that it might have spent the winter there.

“As temperatures warm up in California and across the United States,” said Trumble, “these insects will be able to overwinter further and further north.”

Meanwhile, down south, farmers have already been hit hard by the pest. In Mexico’s Baja California, the psyllids destroyed 85 percent of the tomato crop in 2001, said Trumble. Partly in response to the new pest, California farmers who grow tomatoes in Baja California have moved much of their production inside screened enclosures.

Spraying for psyllids is costing California potato growers about $75 per acre, said Kirschenmann.

Potato field in New Cuyama Valley, an hour southwest of Bakersfield. Potato-tomato psyllids have been found nearby. Photos: Gabriela Quirós.

This need for additional spraying has Trumble concerned. Since the 1970s, he and other scientists around the state have worked with growers to reduce pesticide use in conventionally-grown crops. The results have been dramatic, he said. Tomato growers, for example, cut spraying by half in the 1990s.

“Less pesticide use means less concern by the consumers for pesticide residue. We use less fossil fuel; we have fewer volatile organic compounds that appear in the atmosphere; it reduces smog. It’s a real win-win for everybody in California,” said Trumble.

But warmer temperatures, and the pests that thrive in them, now threaten to undermine these gains.

“So if you have an insect with multiple generations, you get more generations. If you’ve got an insect that occurs early in a crop, it will occur earlier in the crop, and faster,” said Trumble. “So all of these things are desperately in need of additional research.”